The below ran in Lucire today, though it is equally suited to the readers of this blog.

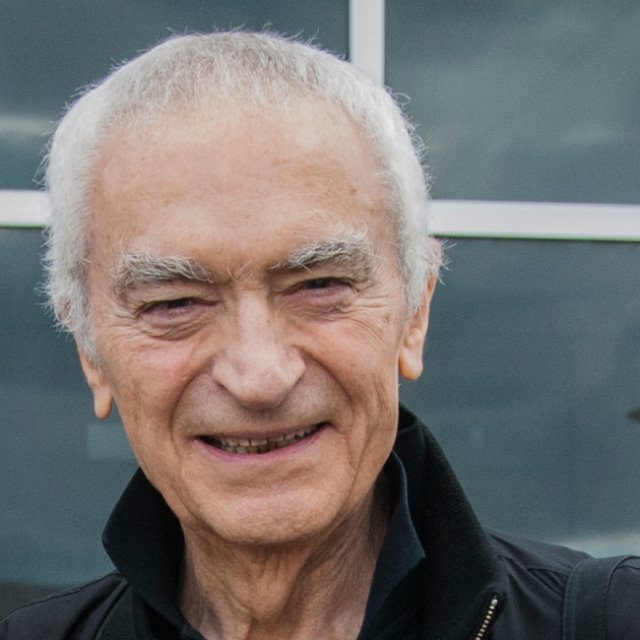

RIT

Massimo Vignelli, who passed away on May 27, was a hero of mine. When receiving the news shortly before it hit the media in a big way, from our mutual friend Stanley Moss, this title’s travel editor and CEO of the Medinge Group, I posted immediately on Facebook: ‘It is a sad duty to note the passing of Massimo Vignelli, one of my heroes in graphic design. When I was starting out in the business, Massimo was one of the greats: a proponent of modernism and simple, sharp typography. His influence is apparent in a lot of the work done by our brand consultancy and in our magazines, even in my 2013 mayoral campaign graphics. A lot of his work from half a century ago has stood the test of time. There was only one degree of separation between us, and I regret that we never connected during his lifetime. The passing of a legend.’

This Facebook status only scratches the surface of my admiration for Vignelli. There have been more comprehensive obits already (Fast Company Design rightly called him ‘one of the greatest 20th century designers’), detailing his work notably for the New York subway map, and—curiously to me—glossing over the effect he had on corporate design, especially in the US.

Vignelli, and his wife Lella, a designer in her own right and a qualified architect, set up the Vignelli Office of Design and Architecture in Milano in 1960, which had clients including Pirelli and Olivetti. In 1965, they moved to New York and Vignelli co-founded Unimark International (with Ralph Eckerstrom, James Fogelman, Wally Gutches, Larry Klein, and Bob Noorda), where he was design director. It was the world’s largest design and marketing firm till its closure in 1977.

The 1960s were a great time for Vignelli and his corporate identities. He worked on American Airlines, Ford, Knoll, and J. C. Penney, and the work was strictly modernist, often employing Helvetica as the typeface family. Vignelli was known to have stuck with six families for most his work—Bodoni was another, a type family based around geometry that, on the surface, tied in to his modernist, logical approach. However, there were underlying reasons, including his belief that Helvetica had an ideal ratio between upper- and lowercase letters, with short ascenders and descenders, lending itself to what he considered classic proportions. The 1989 WTC Our Bodoni, created under Vignelli’s direction by Tom Carnase and commissioned by Bert di Pamphilis, adheres to the same proportions.

Although my own typeface design background means that I could not adhere to six, there is something to be said for employing a logical approach to design. American corporate design went through a “cleaning up” in the 1960s, with a brighter, bolder sensibility. Detractors might accuse it of being stark, the Helveticization of American design making things too standard. Yet through the 1970s the influence remained, and to my young eyes that decade, this was how professional design should look, contrary to the low-budget work plaguing newspapers and books that I saw as I arrived in the occident.

When the Vignellis left Unimark to set up Vignelli Associates in 1971 (and later Vignelli Designs in 1978), their stamp remained. The MTA launched Vignelli’s subway map the following year, and like the London Underground map by Harry Beck in 1931, it ignored what was above ground in favour of a logical diagram with the stops. Beck was a technical draftsman and the approach must have found favour with Vignelli, just as it did with those creating maps for the Paris Métropolitain and the Berlin U-bahn.

New Yorkers didn’t take to the Vignelli map as well as Londoners and Parisians, and it was replaced in 1979 with one that was more geographically accurate to what was above ground.

In 1973, Vignelli worked on the identity for Bloomingdale’s, and his work endures: the Big Brown Bag is his work, and it continues to be used by the chain today. Cinzano, Lancia and others continue with Vignelli’s designs.

Ironically, despite a rejection of fashion in favour of timelessness, some of the work is identified with the 1960s and 1970s, notably thanks to the original cut of Helvetica, which has only recently been revived (a more modern cut is commonplace), and which is slightly less popular today. Others, benefiting from more modern layout programs and photography, look current to 2010s eyes, such as Vignelli Associates’ work for the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

The approach taken by Lucire in its print editions has a sense of modernism that has a direct Vignelli influence, including the use of related typeface families since we went to retail print editions in 2004. Our logotype itself, dating from 1997, has the sort of simplicity that I believe Vignelli would have approved of.

Vignelli was, fortunately, fêted during his lifetime. He received the Compasso d’Oro from ADI twice (1964 and 1998), the AIGA Gold Medal (1983), the Presidential Design Award (1985), the Honorary Royal Designer for Industry Award from the Royal Society of Arts (1996), the National Lifetime Achievement Award from the Cooper–Hewitt National Museum of Design (2003), among many. He holds honorary doctorates from seven institutions, including the Rochester Institute of Technology (2002). Rochester has a Vignelli Center for Design Studies, whose website adheres to his design principles and where educational programmes espouse his modernist approach. It also houses the Vignellis’ professional archive.

He is survived by his wife, Lella, who continues to work as CEO of Vignelli Associates and president of Vignelli Designs; their son, Luca, their daughter, Valentina Vignelli Zimmer, and three grandchildren.