Forty-three years ago (September 16, 1976), we arrived in this country.

As we flew from Sydney and into Wellington, my Dad pointed out the houses below to me. ‘See, those are the sorts of houses New Zealanders live in,’ he said. I thought it was odd they lived in two-storey homes and not apartment blocks. I was three at the time, so I had no clue about the population density of Aotearoa.

I frequently point out just how cloudy and grey that day was. I don’t remember a summer of ’76–’77, just as no one here remembers a summer of ’16–’17. Only one other car, a Holden station wagon, went along Calabar Road in the opposite direction as we left Wellington Airport.

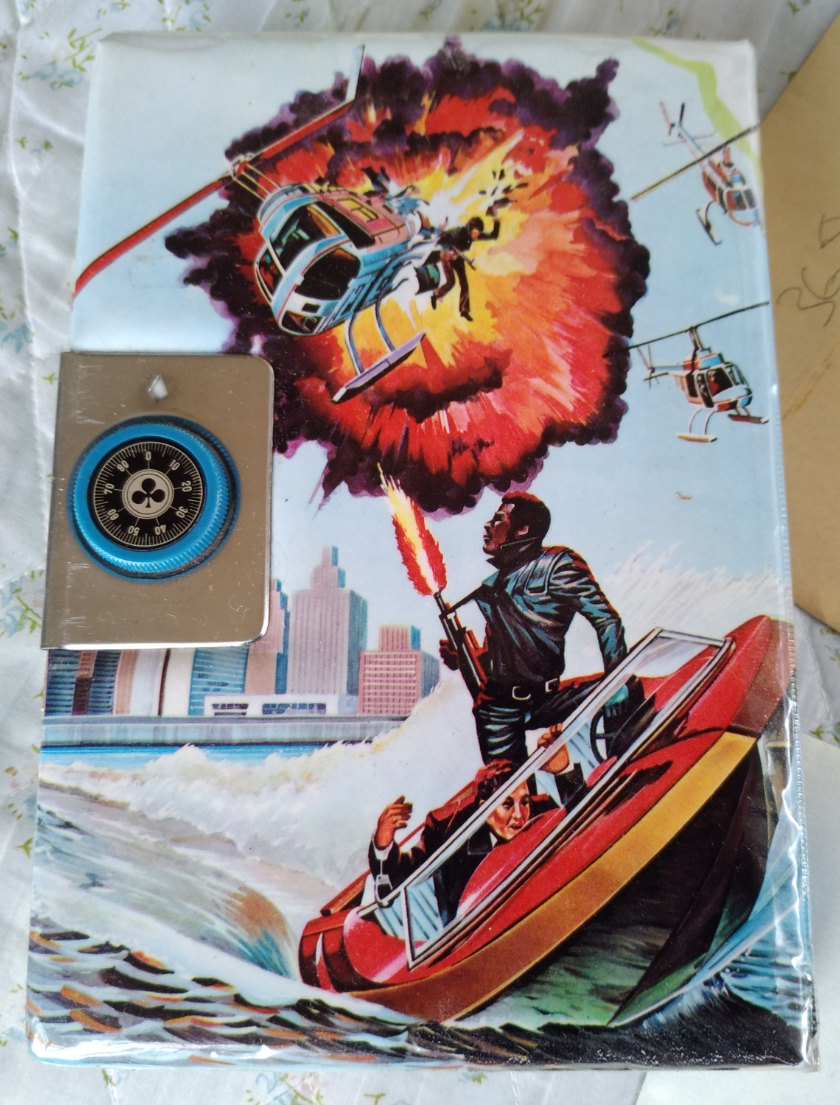

Before we departed Hong Kong days earlier, my maternal grandmother—the person closest to me at that point and whom I would desperately miss for the next 18 months—gave me two very special Corgi models at the airport, large 1:36 scale Mercedes-Benz 240Ds. I said goodbye to her expecting to see her in weeks.

As I was put to bed that night by my father—it wasn’t usually his role—he asked if I wanted to see the cars, since I had been so good on the flights. He got them out and showed me, and I was allowed to have a quick look before they were put back into his carry-on bag.

None of us knew this was the trip where we’d wind up in Aotearoa. Mum had applied—I went with her to the New Zealand High Commission in Connaught Tower in Hong Kong to get the forms—but we had green cards to head to Tennessee. But, my mother, ever careful, didn’t want to put all her eggs into one basket. And like a lot of Hong Kongers at the time, they had no desire to hang around till 1997 and find themselves under communist rule.

It was a decision that would change our lives.

Whilst here, word got back home—and then out to us—that New Zealand immigration had approved our application. In the days when air travel cost a fortune, my parents considered our presence here serendipitous and decided to stay. What point was there to fly back if one’s only task was to pack?

It’s hard not to reminisce on this anniversary, and consider this family with their lives ahead of them.

I’ve had it good. Mum never wanted me to suffer as she had during the famine behind the Bamboo Curtain, and to many in the mid-1970s, getting to the Anglosphere was a dead cert to having a better life.

I had a great education, built a career and a reputation, and met my partner here, so I can’t complain. And I couldn’t have asked for more love and support than I had from my immediate family.

My grandmother eventually joined us under the family reunion policy in 1978. My mother and I were her only living descendants.

Despite the happiness, you don’t think, on that night in 1976, that in 18 years my mother would die from cancer and that my widowed father, at 80, would develop Alzheimer’s disease, something of which there is no record in the family.

Despite both parents having to make the decision to send a parent to a rest home, when it came time for me to do the same thing—and it was the right decision given the care Dad needed—it was very tough.

A friend asked me how I felt, and I said I felt like ‘the meanest c*** on earth,’ even though I knew I would have made the same decision regardless of other factors as his disease progressed.

Immigrant families stick together because we often have the sense of “us versus the world”. When Racist ’80s Man tells you to go back to where you came from, it’s not an experience you can easily share with others who aren’t immigrants and people of colour. So as our numbers diminished—my grandmother in 1990 and my mother in 1994—it was Dad and me versus the world, and that was how we saw things for the decades that followed.

That first night he went to live in a home was the same night I flashed back to the evening of September 16, 1976—and how impossibly hard it would have been to foresee how things would turn out.

He’s since changed homes twice and found himself in excellent care at Te Hopai, though he now needs to be fed and doesn’t detect as much to his right. The lights are going out.

It’s a far cry from being the strong one looking after your three-year-old son and making sure he could fall asleep in this new country, where things were in such a state of flux.

One thought on “First night”