I decided there’d be no harm getting that Facebook archive since I was no longer using it. And while I didn’t see phone logs as Dylan McKay did (I only had the app for about a month or so in 2012), what I did find was entirely in line with the privacy breaches I had been accusing Facebook of for years.

It relates to the Facebook ad preferences. In December 2016, I filed a complaint with the US Better Business Bureau over the fact that Facebook continued to compile data on your advertising preferences even after you opted out. During 2016, Facebook repopulated all my preferences not once, but multiple times, and I found a direct link between one of the advertisements it displayed in my feed and the recompiled preferences. This was the “smoking gun” the BBB asked me to find, though I never heard back from them.

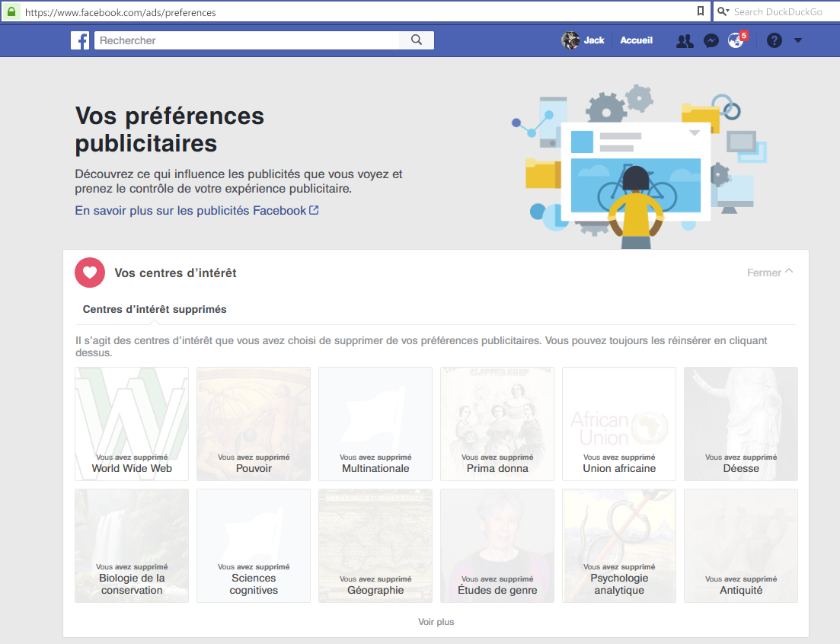

As of 2018, knowing that Facebook will not respect your opt-outs, just as Google failed to do in 2011 (and potentially for two years before that), I visited the ad preferences’ page (here’s the link to yours, if you use Facebook and are logged in) regularly to keep it empty. What the download showed was very damning: Facebook has preferences compiled on me that do not appear on its ad preferences’ page.

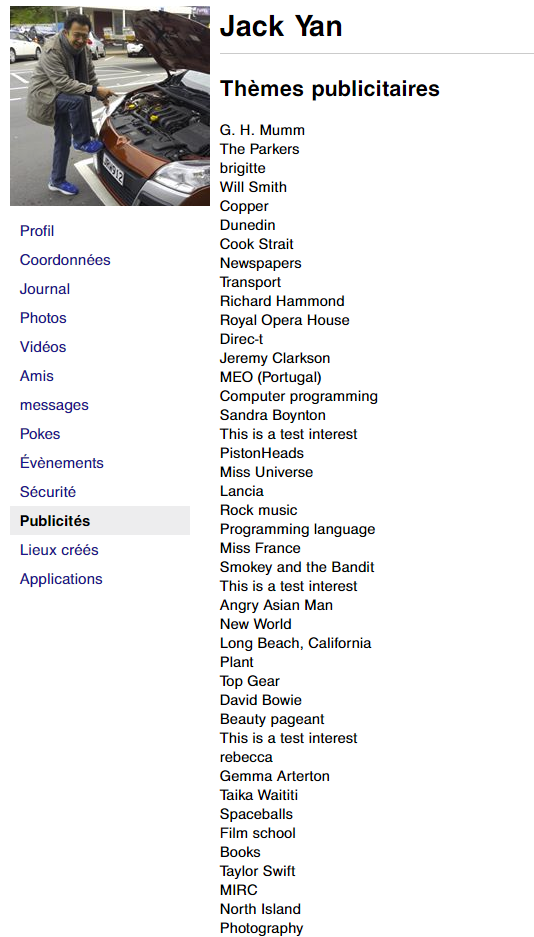

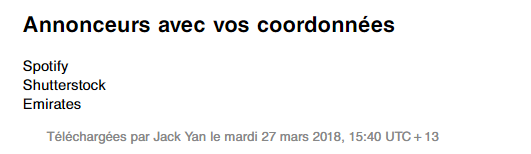

Below are two screen shots, one of Facebook’s ad preferences’ page, and what is recorded in the archive. This is a direct violation of not only what the BBB says is one of its principles, it is a violation of the code advertisers subscribe to in industry bodies like the Network Advertising Initiative.

Above: Facebook’s own advertising preferences’ page, yet its user archive records something entirely different.

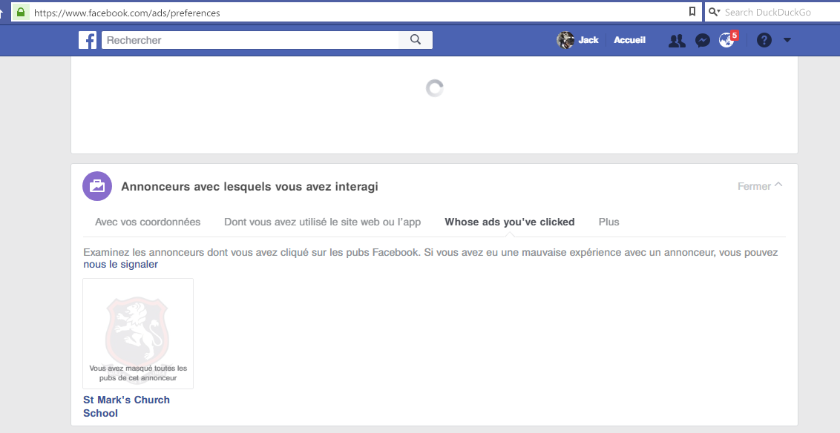

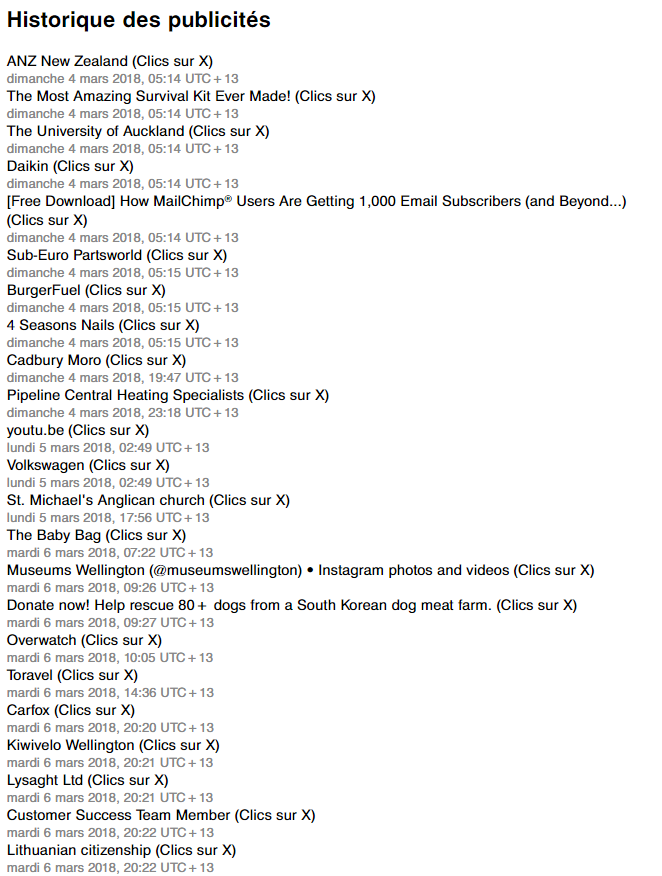

The archive is also interesting in claiming what ads I have supposedly interacted with. The ad preferences’ page says I have only clicked on an ad from my Alma Mater, St Mark’s Church School. The download says otherwise, recording clicks but not describing which device. However, I can categorically state that the downloaded record is 100 per cent false. I have not only never clicked on those ads (in either Facebook or on Instagram), I have not heard of some of these organizations. It is tempting, therefore, to conclude that if this is Facebook’s record of my activity, then it is misrepresenting click activity to advertisers, which I regard as extremely dishonest. We already know Facebook lies about users that ads can reach. Even if you don’t take my word for it, then you must ask yourself why the Facebook page and the Facebook download tell two very different stories. Which is right?

It’s the same story when it comes to which advertisers I have interacted with. The second list, in the user archive, is 100 per cent false. Has Facebook lied to advertisers over click activity?

This is not the end of it. As to which advertisers have my contact information, the ad preferences’ page say none. The download, however, says Spotify (which I have never used or downloaded), Shutterstock (whose site I have been on) and Emirates (and I am on their email list, but separately from Facebook). Again, why the two different records? And why has Facebook passed on this information to three advertisers without my consent?

Once again, when it comes to who has my contact information, Facebook tells me one story on an easily accessible page, and another one inside my user data archive. Which is true?

While most people will be less shocked by these revelations—I realize most are quite happy for Google et al to track them around the place and feed them content to confirm their own biases—it is still a violation of trust and the principles that Facebook itself has signed up to.

It’s another case of ‘I told you so’: something that I suspected, found some evidence for, and found even more evidence for today.

Like the malware scanner, the subject of my blog post in 2016 and Louise Matsakis’s exposé in Wired last month, Facebook needs to come clean on why it compiles data on users who have used its own settings to opt out, why it lies to users over what those preferences are, and why it may lie to advertisers about user click activity.

We know the answer is money. As I said in December 2016, I have no problem with Facebook making money. I just ask, as I do with any venture, that it does so honestly. Right now, even with all the data it has on us, it appears Facebook can’t even do that right.

2 thoughts on “Facebook’s ad preferences’ page and user archive tell totally different stories about their tracking”