Hernán Piñera/Creative Commons/CC BY-SA 2.0

My friend Richard MacManus wrote a great blog post in February on the passing of Clive James, and made this poignant observation: ‘Because far from preserving our culture, the Web is at best forgetting it and at worst erasing it. As it turns out, a website is much more vulnerable than an Egyptian pyramid.’

The problem: search engines are biased to show us the latest stuff, so older items are being forgotten.

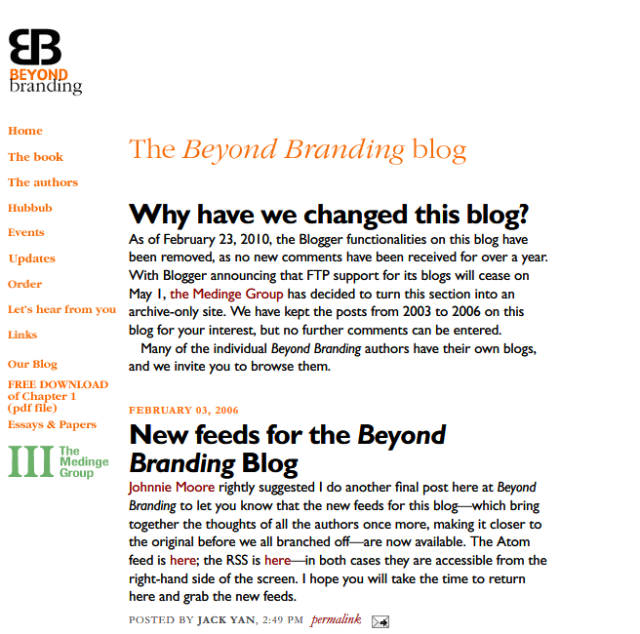

There are dead domains, of course—each time I pop by to our links’ pages, I find I’m deleting more than I’m adding. I mean, who maintains links’ pages these days, anyway? (Ours look mega-dated.) But the items we added in the 1990s and 2000s are vanishing and other than the Internet Archive, Richard notes its Wayback Machine is ‘increasingly the only method of accessing past websites that have otherwise disappeared into the ether. Many old websites are now either 404 errors, or the domains have been snapped up by spammers searching for Google juice.’

His fear is that sites like Clive James’s will be forgotten rather than preserved, and he has a point. As a collective, humanity seems to desire novelty: the newest car, the newest cellphone, and the newest news. Searching for a topic tends to bring up the newest references, since the modern web operates on the basis that history is bunk.

That’s a real shame as it means we don’t get to understand our history as well as we should. Take this pandemic, for instance: are there lessons we could learn from MERS and SARS, or even the Great Plague of London in the 1660s? But a search is more likely to reveal stuff we already know or have recently come across in the media, like a sort of comfort blanket to assure us of our smartness. It’s not just political views and personal biases that are getting bubbled, it seems human knowledge is, too.

Even Duck Duck Go, my preferred search engine, can be guilty of this, though a search I just made of the word pandemic shows it is better in providing relevance over novelty.

Showing results founded on their novelty actually makes the web less interesting because search engines fail to make it a place of discovery. If page after page reveals the latest, and the latest is often commodified news, then there is no point going to the second or third pages to find out more. Google takes great pride in detailing the date in the description, or ‘2 days ago’ or ‘1 day ago’. But if search engines remained focused on relevance, then we may stumble on something we didn’t know, and be better educated in the process.

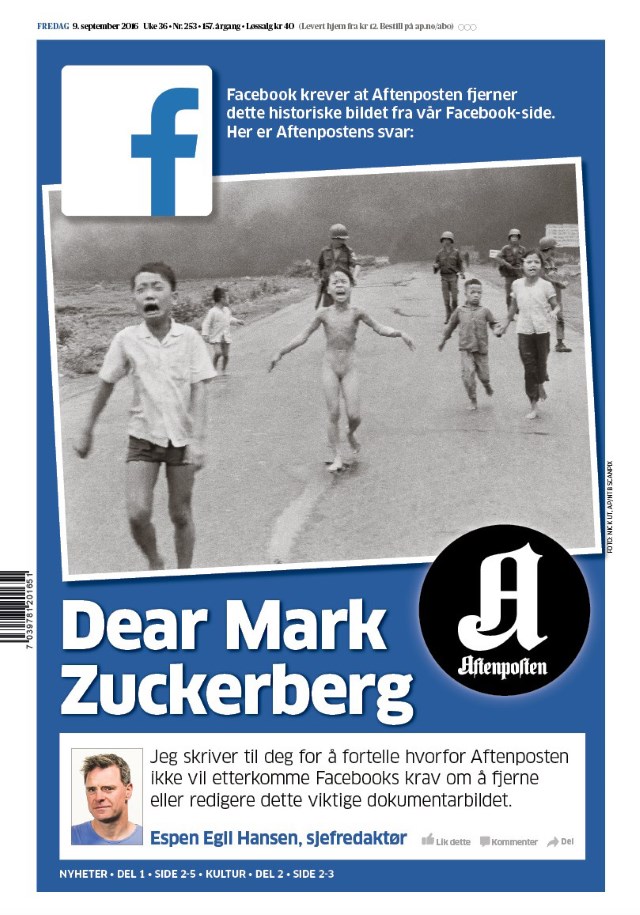

Therefore, it’s possibly another area that Big Tech is getting wrong: it’s not just endangering democracy, but human intelligence. The biases I accused Google News and Facebook of—viz. their preference for corporate media—build on the dumbing-down of the masses.

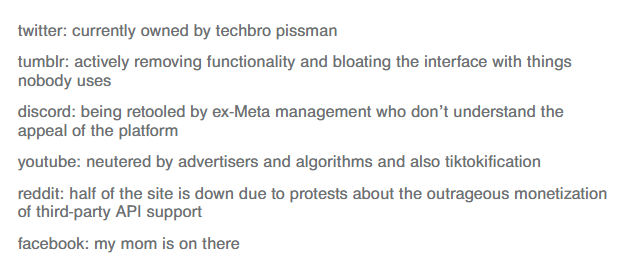

I may well be wrong: maybe people don’t want to get smarter: Facebook tells us that folks just want a dopamine hit from approval, and maybe confirmation of our own limited knowledge gives us the same. ‘Look at how smart I am!’ Or how about this collection?

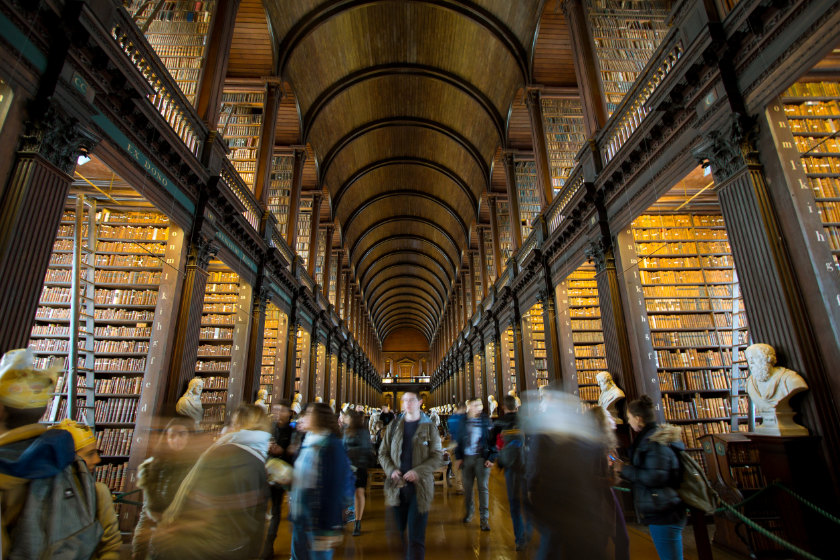

Any expert will tell you that the best way to keep your traffic up is to generate more and more new content, and it’s easy to understand why: like a physical library, the old stuff is getting forgotten, buried, or even—if they can’t sell or give it away—pulped.

Again, there’s a massive opportunity here. A hypothetical new news aggregator can outdo Google News by spidering and rewarding independent media that break news, by giving them the best placement—as Google News used to do. That encourages independent media to do their job and opens the public up to new voices and viewpoints. And now a hypothetical new search engine could outdo Google by providing relevance over novelty, or at least getting the balance of the two right.

One thought on “Even the web is forgetting our history”