Above: Dementia Wellington’s support has been invaluable.

Today my father turned 83.

It’s a tough life that began during the Sino–Japanese War, with his father being away in the army, and his mother and grandmother were left to raise the family on their land in Taishan, China.

In 1949, the Communists seized the property and the family had to start again, as refugees, in Hong Kong.

Ever the entrepreneur, during the Vietnam War, Dad and his business partner, an US Army doctor by the name of Capt Dr Lawson McClung, set up a mail-order business for deployed troops. As I recall it, Lawson said that he would be able to secure jobs for my parents—my late mother was a nurse—at his stepfather’s hospitals in Tennessee. We either had a US green card, or one was merely procedural.

My mother realized we had family in Aotearoa and I remember going with her to Connaught Tower, to the New Zealand High Commission. I didn’t know what it was for, but filling in the gaps it must have been to secure forms for immigration. As Plan Bs go, it was a pretty good one.

In 1976 came another move as we headed to New Zealand, originally on holiday, given that my grandfather had taken ill whilst here. As we flew in to Wellington, Dad pointed at the houses below. ‘Those are the sorts of houses New Zealanders live in.’ I thought it was fascinating, that they didn’t live in apartment blocks.

That first night here, on September 16, 1976, it was Dad who tucked me in, which at this point wasn’t typical: it was usually my grandmother who did this. He asked if I wanted to see the two Corgi toy cars that my grandmother had bought me prior to the trip, which I could have if I behaved myself on the flights. I did. He took them out of the luggage and I had a brief look at them. This was an unfamiliar place but it was just a holiday and things would be back to normal soon.

It was during this holiday that word came that our immigration application had come through. My parents regarded our presence here as serendipitous. They neglected to tell their four-year-old son that plans had changed.

For the first 18 years of my life, I regarded ‘the family’ as being my parents and my widowed maternal grandmother, who lived with us ever since I could remember—and I remember an awfully long time. We even had a photo taken around 1975–6 of the four of us, that I just remember represented everyone dearest to me.

As ‘the family’ lost one member to a stroke brought on by Parkinson’s disease and complications from diabetes, and another to cancer, by 1994 it was just Dad and me.

At the beginning of the 2010s, Dad had a bout of shingles. By 2014 he was forgetting individual words, and I insisted he get checked out for dementia. Around the time of his 80th birthday, in 2015, the diagnosis from the psychogeriatrician was formal, although he could still speak with some stuttering and one or two words unreachable by his brain. The CT scans showed a deterioration of the left side of his brain, his speech centre. Within half a year there would only be one or two words per sentence that were intelligible.

The forms for an enduring power of attorney were drawn up as 2016 commenced. He was still managing, and he had his routines, but in mid-2018 we decided he should get some respite care.

He wasn’t happy about this, and it took four hours of persuading, as well as a useful and staunch aunt, who got Dad to put on his shoes and head up with us to Ultimate Care Maupuia.

We had thought the second visit in late July would be easier but it took 19 hours over two days, an experience which we do not want to repeat.

Dad had lost the ability to empathize with us and was anxious and agitiated. While he insisted he could look after himself while home alone, there were signs over the last year that indicated he could not. He fell while having the ’flu in mid-2017 and Amanda and I came to a house with all its lights off. We had no idea how long he had been down. By 2018 he would cry if left home alone. Even at his most insistent that he could look after himself, we returned after the first day of trying to coax him to Maupuia to find that he had not eaten.

The second day was when I called everyone I could think of to find a way to get to respite, since we weren’t going to be around to look after him.

You name it, I called it, Age Concern aside.

Dementia Wellington, the police, the rest home, Wellington Free Ambulance, Driving Miss Daisy, Care Coordination, Te Haika, and so on. I spoke to 11 people that day.

Te Haika said that the issue wasn’t mental, but legal, which was about as useful as telling an American Democrat that Donald Trump was the Messiah.

Driving Miss Daisy said that I wasn’t in their area but a colleague was, not that I ever heard back from that colleague.

Dementia Wellington, the police, and Free Ambulance were brilliant, as was my lawyer, Richard Brandon of Brandons. Our GPs at Kilbirnie Medical Centre were also excellent.

The up shot was that Free Ambulance could take Dad if the enduring power of attorney was enacted, and that would take a declaration of mental incapacity by the GP, which was duly written. He was also good enough to prescribe some medication to calm Dad down.

However, because it wasn’t an emergency situation, there was no telling when Free Ambulance could come by.

It did make me glad that they were one of the charities I gave to this year.

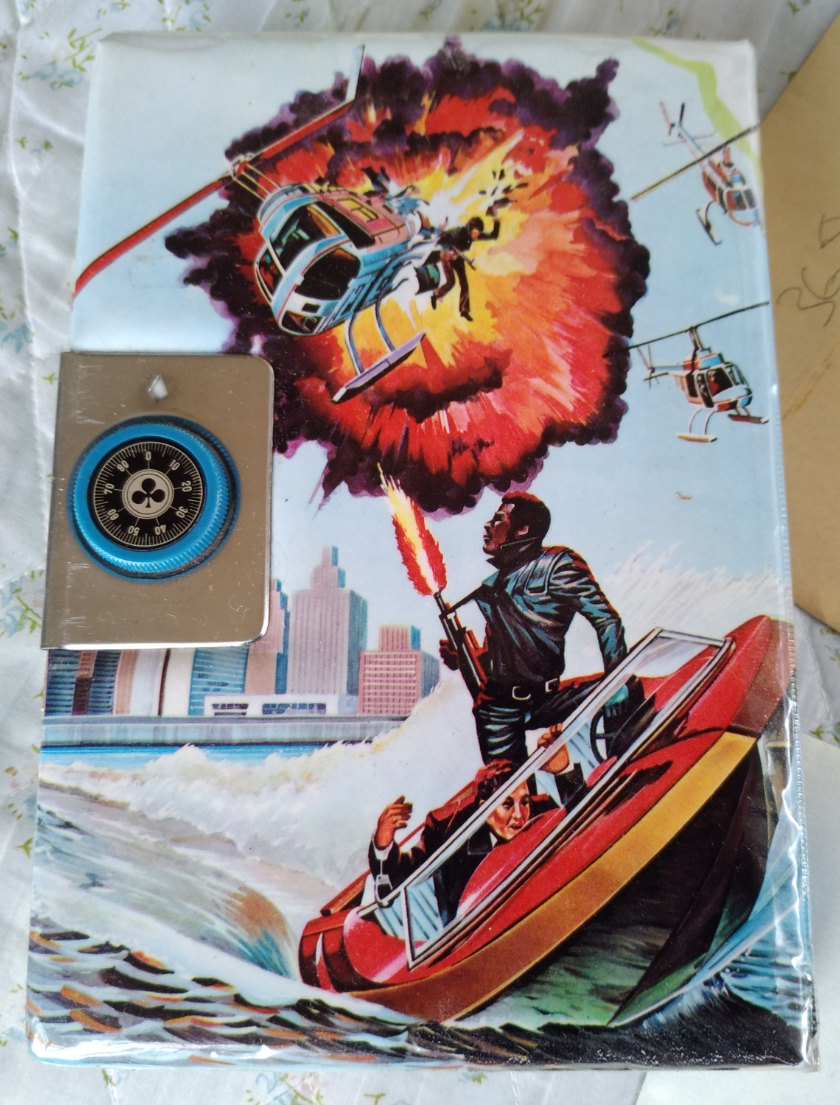

However, you don’t ever imagine a situation where you effectively drug your Dad to be able to put his jacket on and take him to a rest home for respite care. I felt like part of the Mission: Impossible team, except the person being drugged wasn’t a Ruritanian dictator, but someone on the same side. When I say Mission: Impossible, I don’t mean that series of films with Tom Cruise, either.

On September 16, 1976, you didn’t think that in 42 years’ time your Dad would have dementia and you’d need to break a promise you made years ago that you would never put him in a home.

You also feel that that photo of ‘the family’ has been decimated, that you’re all alone because the last adult in there isn’t around any more for you to bounce ideas off and to have a decent conversation with.

I realize I hadn’t been able to do any of that with Dad for years but it feels that much more painful knowing he can’t live in a place he calls home presently.

And you also realize that as a virtually full-time caregiver who has cooked for him for years—and now you know why I didn’t reenter politics in 2016—that his condition really just crept up on you to a point where what you thought was normal was, in fact, not normal at all.

You also realize that the only other time he was compelled to leave his home without his full volition was 1949, by a régime he had very little time for through most of his lifetime. You don’t expect to be the next person to have to do that to him, and there’s a tremendous amount of guilt that comes with that.

Earlier this week, our GP reissued his letter in ‘Form 5’ (prescribed under the Protection of Personal and Property Rights Act 1988), which I drafted, since these procedures aren’t altogether clear. It makes you wonder how people without law degrees might cope. Tomorrow I will meet with Care Coordination and see if Dad can be reassessed based on his current condition. He was only very recently assessed as not needing long-term care so it will be interesting to see if they accept that he has deteriorated to this extent. I’m not a Mystic Meg who can make a prediction on this.

The rapidity of Dad’s change—one which he himself noticed, as years ago he would complain that his ‘brain felt different today compared to yesterday’—has been a surprise to us, although mostly he is happy at Maupuia and interacts positively with the staff. It’s not all smooth sailing and there are days he wonders when he can come home.

And I find some solace in that his father, and his mother-in-law, wound up in care for less. My grandfather had PTSD from the war and was unable to cook for himself, though even at the end he was bilingual (being educated in the US) and had successfully quit smoking after 70 years. My grandmother needed care because of her insulin injections but was also mentally fit.

But part of me expected that I’d see it through with Dad to the end, that these rest homes were some western thing that separated families, and here is part of that immigrant experience.

The reason you didn’t see as many Chinese New Zealanders on welfare wasn’t down to some massive savings’ account, but a certain pride and stoïcism in being to keep it to yourself. You’re in a strange land where there’s prejudice, and that’s often enough for families to say, ‘F*** everyone else, we’re getting on with it and doing it ourselves.’

And that’s what we did as ‘the family’. We fought our own battles. Dad was once a helluva correspondent whose letters used words like proffer and the trinity of ult., prox. and inst., and plenty of officials got the sharp end of his writing. When Mum got cancer we brought in our own natural medication because westerners couldn’t fathom that the same stuff cleared my grandfather’s liver cancer in 1976 and healed several other members in the whānau. Dad sacrificed everything to try to save Mum and that was the closest example I had of what you’d do for someone you love.

When you’re deep in the situation, rationality goes out the window and you’re on autopilot—and often it takes serious situations, like two days’ angst and stress of trying to get someone into respite care, to make you think that staying at home isn’t the best for someone who did, even though he won’t admit it, thrive under rest home care.

We know that if we left it even later, it would be even tougher to get Dad into care and he would resist his new surroundings more.

Today’s lunch at Maupuia was curried beef on rice in recognition of Indian Independence Day, a much nicer meal than what I might have made for Dad.

He has staff to hug and laugh with even if I have no idea where he’s putting his dirty undies.

And while aphasia means he hasn’t made any new friends yet, I have faith that he’ll do well given the circumstances.

It’s those circumstances that mean the situation we find ourselves in, with Dad at the home, is one which we’ll roll with, because, like 1949 and 1976, forces outside our control are at play.

I’d love to make his Alzheimer’s go away given that I already lost one parent prematurely.

My mind goes to a close friend who recently lost her mother, and her father was killed in a car crash around the time my Mum died. Basically: not all of us are lucky enough to have both our parents peacefully go in their sleep. Many of us are put through a trial. And there’s a real reason some of us have been hashtagging #FuckAlzheimers on Twitter, if out of sheer frustration.

For those who have made it this far, here are the points I want you to take away.

• Immediately upon finding out your parent has dementia, get your enduring power of attorney sorted out, for both property and personal care.

• Dementia Wellington is an excellent organization so get yourself along to the carer support groups, second Monday of every month. Dementia New Zealand can’t help at this level.

• Care Coordination has been very helpful and their referral to Dementia Wellington proved more effective than phoning—however, I should note that the organization changed for the better between Dad’s original diagnosis in 2015 and how they are today.

• You do need ‘Form 5’ from your GP or someone in a position to assess your parent’s mental capacity to kick off the enduring power of attorney.

• It’s OK to cry, feel emotionally drained and ask your friends for support. It’s your parent. You expected to look after them and sometimes you need to let others do this for everyone’s good. It doesn’t mean you love your parent any less. It also doesn’t mean you are placing yourself or your partner above him. It just means you are finding the best solution all round.

Dad is still “there”, and he recognizes us, even if he doesn’t really know what day it is, can’t really cook for himself, and doesn’t fully understand consequences any more. I’m glad I spend parts of every day with him while I’m in Wellington. And while this wasn’t the 83rd birthday I foresaw at the beginning of the year, he is in a safe, caring environment. I hope the best decision is made for him and for all of us.