A generation ago, I don’t think many would have thought that globalization could be brought to its knees by a virus. They may have identified crazy politicians using nationalism as a tool, but probably considered that would not happen in developed economies and democracies sophisticated enough to withstand such assaults.

This course correction might be poetic to the pessimist. Those who emptied their own nations’ factories in favour of cheaper Chinese manufacture perhaps relied on appalling conditions for their working poor; and if China were incapable of improving their lot—and you can argue just why that is—then with hindsight it does not seem to be a surprise that a virus would make its leap into humankind from Wuhan, itself not the shiny metropolis that we might associate with the country’s bigger cities. Those same corporations, with their collective might, now find themselves victim to an over-reliance on Chinese manufacture at the expense of their own, with their primary, and perhaps only, country of manufacture no longer producing anything for them as the government orders a lock-down.

I argued months ago that failing to declare the coronavirus as a matter of international concern a week before the lunar New Year was foolhardy at best; perhaps I should have added deadly at worst. Here is the period of the greatest mobilization of humans on the planet, and we are to believe this is a domestic matter? If capitalist greed was the motive for downplaying the crisis, as it could have been within China when Dr Li Wenliang began ringing alarm bells on December 30, 2019 and was subsequently silenced, then again we are reaping the consequences of our inhumanity: our desire to place, if I may use the hackneyed expression, profits above people. And even if it wasn’t capitalism but down to his upsetting the social order—the police statement he was forced to sign said as much—the motive was still inhuman. It was the state, as an institution, above people and their welfare.

We arrive at a point in 2020 where one of Ronald Reagan’s quotes might come true, even if he was talking about extraterrestrials. At the UN in 1987, President Reagan said, ‘Perhaps we need some outside universal threat to make us recognize this common bond. I occasionally think how quickly our differences worldwide would vanish if we were facing an alien threat from outside this world.’

This might not be alien, but it is a universal threat, it is certainly indiscriminate and it affects people of all creeds and colours equally.

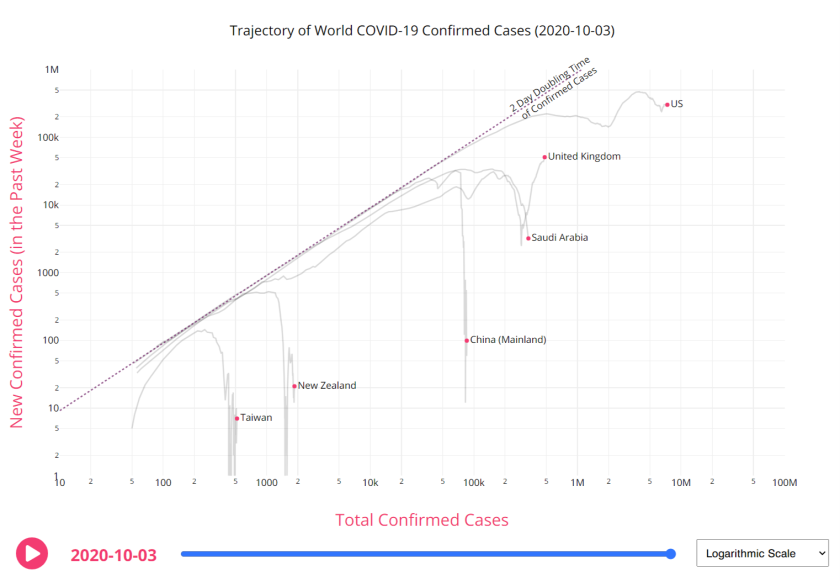

Our approaches so far do not feel coordinated globally, with nations resorting to closing borders, which prima facie is sensible as a containment measure. You would hope that intelligence is being shared behind the scenes on combatting the virus. I’m not schooled enough to offer a valuable opinion here so I defer to those who are. But I’m not really seeing our differences vanish, even though we are being reminded at a global level of the common bond that Reagan spoke of. This is a big wake-up call.

Examining the occidental media, there appears to be a greater outcry over President Donald Trump closing the US from flights from the EU Schengen zone than there was when China faced its travel ban, suggesting to me that barring your nation from people within a group of 420 million is a bigger deal than barring people from a group of 1,400 million. One lot seems more valued than the other lot.

What I do believe is that we have made certain choices as a people, and that while the pure model of globalization raises standards of living for all, we, through our governments and institutions, haven’t allowed it to happen. We’ve not seen level playing fields as we were promised. We’ve seen playing fields dominated by bigger players, and for all those nations that are sucked into the prevailing mantra that arose in the 1980s, we’ve allowed our middle classes to shrink and the gap between rich and poor to grow. The one economic group that assures prosperity has been eroded.

As it’s eroded then we’re looking at economies that favour the rich and their special interest groups over the poor, rather than investing in public infrastructure and education.

No wonder many lack faith in their institutions, and their willing and continued pursuit of the monetarist order over humanistic agenda.

Yet at the one-to-one level many differences disappear. It’s not helped by social media, those corrosive corporations that seek to separate through algorithms that encourage tribalism, but those that take the time to have a dialogue realize that we are in this together. Within these elaborate websites lies some hope.

My entire working career to date has been mostly one where individuals and independent enterprises have formed contracts to do business, creating things that once didn’t exist through intellectual endeavour. We have done so outside elephantine multinationals, within which many imaginations have been stifled. We are people who can think outside the square—and all too often, the inhabitants of the square reject us anyway.

When the world comes back online, I hope we have learned some lessons about the source of our troubles. We’ve willingly let certain institutions get too big at our expense; we’ve allowed a playing field slanted in their favour that encourages a race to the bottom by outsourcing to underpaid people; and as a result we’ve allowed unhygienic conditions to flourish because they’re “over there”, instead of holding corporations and nations to account. It will take us making choices with our eyes open about policies that champion individuals over big corporations; genuinely creating level playing fields where entrepreneurship can flourish at every level and benefit all; ensuring that we properly fund education and other long-term investments; and having strong foreign policies that can constructively call out injustices by suggesting a better way. We need to do this over the long term. The big corporations have mustered global power and so must individuals. Nationalism is not the answer to solving our problems: it is a reaction, a false glimpse into the past with rose-coloured glasses. It is no more a reflection of our past than a young northern lad pushing his bicycle uphill to Dvořák’s ‘New World Symphony’. Nostalgia is often inaccurate.

Whether you are on the left or the right, whether you love Trump or Sanders, Ardern or Bridges, we’re simply lying to ourselves if we think the other political side is our enemy, when it’s in fact institutions, political or corporate, that have grown too distant to be concerned with anyone but those in power.

Call me an idealist, but we could be on the verge of a humanistic revolution where we use these technological tools for the betterment of us all. Greta Thunberg has done so for her agenda, and we have a chance to, too: a global effort by individuals who see past our differences, because we have those common bonds that Reagan spoke of. Let’s debate the facts and get us on track, resisting both statism and corporatism at their extremes, since they’re sides of the same coin. What empowers us as individuals? In the system we have today, is there a party that can best deliver this? Who’ll keep the players honest? When we start asking these in the context of the pandemic, the answer won’t be as clear as left and right. And I’m not sure if the answer can even be found in major political parties who wish to deliver more of the same, plus or minus 10 per cent.

Or we can wait for the coronavirus to disappear, carry on as we had been, keep dividing on social media to help line Mark Zuckerberg’s pockets, and allow another pandemic to venture forth. It can’t be business as usual.