When I attended Sir Paul Callaghan’s talk at the Wellington Town Hall last September, I felt vindicated. Here was a man who was much better qualified than me to talk about economic development, effectively endorsing the policies I ran on in 2010. But not being political, he was a great deal more persuasive. Since then, I’ve noticed more New Zealanders become convinced by Sir Paul’s passion—and wake us up to the potential that we have in this nation.

This great communicator, this wonderful patriot, this sharpest of minds, passed away today after a battle with colon cancer.

I wrote on Facebook when I heard the news that the best thing we can do to honour Sir Paul was to carry on his legacy, and to carry out the dream he had for making New Zealand a better, more innovative nation.

Sir Paul wasn’t afraid of tall poppies. He knew Kiwis punched above their weight, and wanted to see more of that happen.

All those tributes today saying his passing is a great loss to the nation are so very accurate—and I hope we’ll continue to see his dream realized.

Sir Paul Callaghan had a vision, but at the more micro level, it’s important to get a grasp on what the market will bear. There is a fine line, of course, between testing a market and relying too much on a rear-view mirror, and Jenny Douché’s new book, Fool Proof, addresses that, with case studies featuring some very successful New Zealand businesses, including No. 8 Ventures, Phil & Ted’s, Cultureflow and Xero. She stresses dialogue and engagement as useful tools in market validation, and she’s so passionate about the importance of her work that she’s donated copies to 200 organizations, including business incubators, economic development agencies, business schools and chambers of commerce nationally. Find out more at foolproofbook.com.

Sir Paul Callaghan had a vision, but at the more micro level, it’s important to get a grasp on what the market will bear. There is a fine line, of course, between testing a market and relying too much on a rear-view mirror, and Jenny Douché’s new book, Fool Proof, addresses that, with case studies featuring some very successful New Zealand businesses, including No. 8 Ventures, Phil & Ted’s, Cultureflow and Xero. She stresses dialogue and engagement as useful tools in market validation, and she’s so passionate about the importance of her work that she’s donated copies to 200 organizations, including business incubators, economic development agencies, business schools and chambers of commerce nationally. Find out more at foolproofbook.com.

A Reuter story today talks about Sweden’s growing inequality in the last 15 years—something I’ve certainly noticed first-hand in the eight-year period between 2002 and 2010.

We often aspire to be like Sweden, but much of that aspiration was based on a nation image of equality and social stability. Certainly since the mid-2000s, that hasn’t been true, as Sweden embarked on reforms that we had done in the 1980s, with selling state assets and cutting taxes.

Inequality, according to the think-tank quoted in the article, has risen at a rate four times greater than that of the US.

The other sobering statistic that came out earlier this year was that Sweden has the worst-performing economy in Scandinavia.

None of this is particularly aspirational any more, and perhaps it brings me back to the opening of this blog entry: Sir Paul Callaghan.

Given that we had the 1980s’ economic reforms, but we have scarcely seen the level playing-field promised us by the Labour government of that era, our best hope is to innovate in order to create high-value jobs. On that Sir Paul and I were in accord. Let’s play in those niches and beat the establishment with smart, clever New Zealand-owned businesses—and steadily achieve that that level playing field that we’re meant to have.

It’s about cities creating environments that foster innovation and understand the climate needed for it to grow, which includes formally recognizing clusters, identifying and funding them, and having mechanisms that can ensure ideas don’t get lost beyond a mere discussion stage—including incubator and educational programmes. The best ideas need to be grown and taken to a global level.

Ah, I hear, many of these agencies already exist—and that’s great. Now for the next step.

It’s also about cities not letting politics get in their way and understanding that the growth of a region is healthy—which means cooperation between civic leaders and an ability to move rapidly, seizing innovation opportunities. It means a reduction in bureaucracy and the realization that much of the technology exists so that time spent on admin can be kept to a minimum (and plenty of case studies exist in states more advanced than us). Right-brained people thrive when they create, not when they are filling in forms. The streamlining of the Igovt websites by the New Zealand Government is move in the right direction.

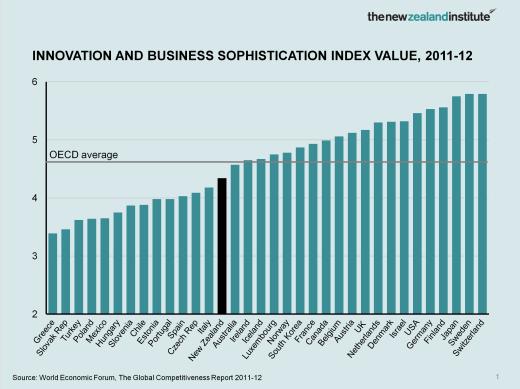

We know what has to be done—especially given how far down we are based on the following graph from the New Zealand Institute:

As the Institute points out, many of the right moves are being made, and have been made, at the national level. But it is also aware that an internationalization strategy is part of the mix—the very sort of policy I have lived by in my own businesses. And this begs the question of why there have not been policies that help those who desire to go global and commercialize their ideas at a greater level. That’s the one area where we need to champion those Kiwis who have made it—Massey’s Hall of Fame dinners over the last two years celebrate such New Zealanders in a small way—and to let those who are at school now know that, when they get into the workforce, that it’s OK to think globally.

If we’re wondering where the gap is, especially in a nation of very clever thinkers, it’s right there: we need to create a means for the best to go global, and make use of our million-strong diaspora, in very high positions, that Sir Paul pointed out in his address. Engagement with those who have made it, and having internationalization experts in our agencies who can call on their own entrepreneurial experiences, would be a perfect start.