People are waking up to the fact that online advertising isn’t what it’s cracked up to be.

Last month, Bob Hoffman’s excellent The Ad Contrarian newsletter noted, ‘I believe the marketing industry has pissed away hundreds of billions of dollars on digital fairy tales and ad fraud over the past 10 years (in fact, I’m writing a book about it.) If I am right, and if the article in question is correct, we are in the midst of a business delusion unmatched in all of history.’ He linked to an article by Jesse Frederik and Mauritz Martin (also sent to me by another colleague), entitled ‘The new dot com bubble is here: it’s called online advertising’ in The Correspondent. In it, they cast doubt over the effectiveness of online ads, hidden behind buzzwords and the selection effect. If I understand the latter correctly, it means that people who are already predisposed to your offering are more likely to click on your ads, so the ads aren’t actually netting you new audiences.

Here’s the example Frederik and Martin give:

Picture this. Luigi’s Pizzeria hires three teenagers to hand out coupons to passersby. After a few weeks of flyering, one of the three turns out to be a marketing genius. Customers keep showing up with coupons distributed by this particular kid. The other two can’t make any sense of it: how does he do it? When they ask him, he explains: “I stand in the waiting area of the pizzeria.”

The summary is that despite these companies claiming there’s a correlation between advertising with them and some result, the truth is that no one actually knows.

And the con is being perpetuated by the biggest names in the business.

As Hoffman noted at the end of October:

A few decades ago the advertising industry decided they couldn’t trust the numbers they were being given by media. The result was the rise of third-party research, ratings, and auditing organizations.

But there are still a few companies that refuse to allow independent, third-party auditing of their numbers.

No surprises there. I’ve already talked about Facebook’s audience estimates having no relationship with the actual population, so we know they’re bogus.

And, I imagine, they partly get away with it because of their scale. One result of the American economic orthodoxy these days is that monopolies are welcome—it’s the neoliberal school of thinking. Now, I went through law school being taught the Commerce Act 1986 and the Trade Practices Act 1974 over in Australia, and some US antitrust legislation. I was given all the economic arguments on why monopolies are bad, including the starvation of innovation in their sector.

Roger McNamee put me right there in Zucked, essentially informing me that what I learned isn’t current practice in the US. And that is worrisome at the least.

It does mean, in places like Europe which haven’t bought into this model, and who still have balls (as well as evidence), they’re happy to go after Google over their monopoly. And since our anti-monopoly legislation is still intact, and one hopes that we don’t suddenly change tack (since I know the Commerce Act is under review), we should fight those monopoly effects that Big Tech has in our country.

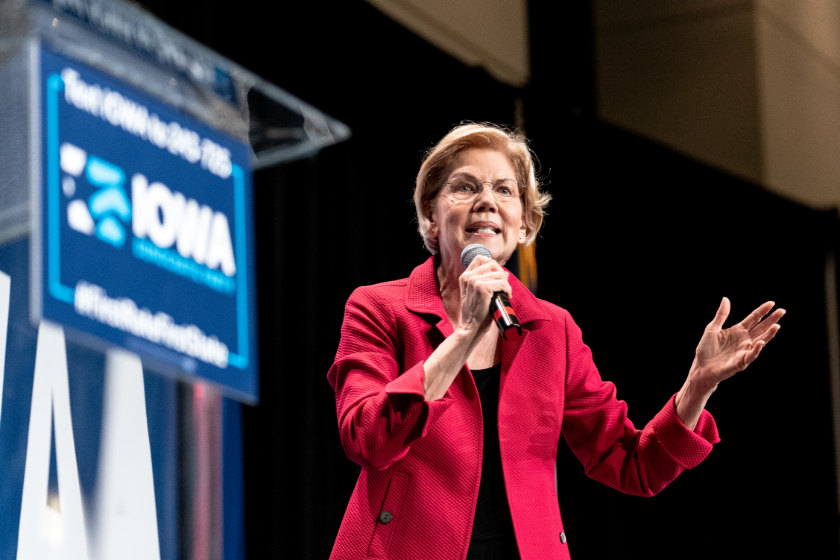

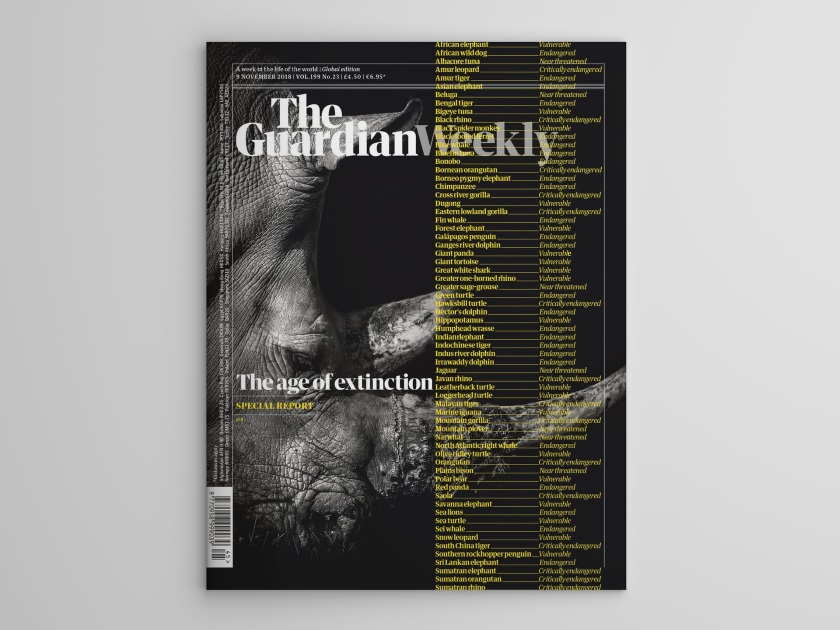

What happens to monopolies? Well, if past behaviour is any indication, they can get broken up. Sen. Elizabeth Warren is simply recounting American history when she suggests that that’s what Facebook, Google and Amazon should endure. There was a time when Republicans and Democrats would have been united on this prospect, given the trusts that gave rise to their Sherman Act in 1890, protecting the public from market failures like these. Even a generation ago, they’d never have allowed companies to get this influential.

Also a generation ago, we wouldn’t swallow the BS an advertising platform gave us without something to back it up. Right now, it seems we don’t have anything—and the industry is beginning to cry foul.

Lorie Shaull/Creative Commons Attribution–Share Alike 2·0

Regardless of your political stripes, Sen. Elizabeth Warren calling for the break-up of Big Tech made sense as recently as a generation ago.

I’d add something. A few years ago when I did some advertising to sell our business in Melbourne we put some adds up on Facebook. Those adds were restricted to;

1. Melbourne and environs.

2. Australia.

The only enquiries for this business we received from Facebook were from third world countries in Asia & Africa (can probably find the screen snaps if you want them). I also know from conversations with others that they’ve experienced the same thing. I suspect that there will be class action against Facebook for this hopefully soon. I think they’re well aware of it, in fact I’m not sure that it’s not part of their business model, and just don’t care. Which tells you everything you need to know about this social media ‘business’.

Thank you, Richard. Your experience is not unlike the case that Veritasium uncovered. They made an experimental page, and went through Facebook, as opposed to an illegitimate click farm, to get likes. The result: they had likes from bots and click farms. Here’s a post I wrote about this back in 2014, along with a link to Veritasium’s video.

Thanks Jack, I just learnt a little by watching that video. Although in our case as all interaction was third world my view is that they were Facebook click farms not accidental hiding of tracks.

But it seems better to have 500 customers gained organically than 3000 customers gained during an advertising campaign.

We’ve never gained anything by advertising on Facebook. One other use of click farms, which we’ve experienced, is that competitors can used them to diss your business.

I imagine it’s in Facebook’s interest to run their own click farms—they are a dodgy bunch. And the more click farms they have, the more people think they have to pay to boost their posts to reach the same number of legitimate users they once did.

I agree, a legitimately and organically gained 500 beat a paid 3,000 any day.

Competitors’ dissing is why I don’t like Google My Business, either. I see way too much potential for abuse. Anyone can ruin your hard-earned reputation anonymously.